Social psychology; The implications for schools planning to ‘return’

With the onset of COVID-19 and the nationally imposed ‘Lockdown’, the organisational culture of the school system changed overnight. Whilst many schools adapted to support key worker needs, they are now being asked to re-boot and revive in some format in anticipation of pupils coming back. How can psychology help school leaders in managing this change? A series of blogs written by Orange Psychology practitioners intend to draw upon social and behavioural insights to inform good practice for school communities in managing ‘the return’ and beyond.

‘Social Norm’ shifting

‘Social norms’ are implicit rules in the social world that ‘give sense’ to what is considered acceptable and unacceptable. Within a school context (and in normal times), examples might be that teachers have authority, children queue for their lunches, and people walk in the corridors etc. These norms help to create behavioural patterns which are predictable and familiar. Boundaries are helpful in creating emotional and psychological safety for children and staff alike. From a social science point of view, one of the biggest challenges facing schools right now therefore is the shifting of these social norms, determined by the new rules of social distancing. Whilst Teacher Trade Unions meet today to discuss the ‘science’ behind decision making, we use a psychological lens to school leaders looking at the impact of shifting social norms on a school system.

‘Cognitive Dissonance’

Operationalising ‘how to social distance in a school’ is front and foremost for all school leaders nationally at this moment in time. But the conflict between providing an emotionally safe and physically safe environment for children is an imminent challenge, and quite likely the route of much cognitive dissonance (Festinger 1957) for parents and staff alike. Whilst schools can take measures to create a virus-responsive environment, in doing so, it threatens to characteristically alter the culture of what defines ‘a school’. As a result, there is a palpable feeling of mental discomfort for school leaders currently, as they push to understand the risks, and ‘do what is right’ at the same time. Feelings of threat are likely to be high across the community of the school system whilst feelings of personal control are low. In these circumstances, (and combined with additional stressful life events within families and communities), stress and anxiety are more likely to be ‘felt’ individually, and systemically within organisations (Powell and Enright 1993). The emotional health of the school is therefore in the balance.

‘Moral Dilemas’

Feelings of discordance are common when looking at research into pandemics. There is often a disharmony between short term self-interest and the ‘collective interest’ of others (Van Lange et al 2018). People are also less willing to make sacrifices for others when the benefits for themselves are still uncertain (Gino et al 2016; Garcia et al 2020). For school leaders, decision making right now is fraught with uncertainty. Balancing the needs of pupils, staff and families whilst processing national and international scientific guidelines is a huge undertaking, and one that cannot be rushed given the implications for error. School leaders need time, they need to talk, and they need support.

School Leader Checklist

The following ideas are taken from behavioural and social sciences and may support school leaders in managing next steps in planning the phases of ‘return’;

Acknowledge and name the changes, but allow for collective processing

Provide explicit recognition of the changing ‘norms’ within your school. Mould them together where possible, as this will assist behavioural change. List them as ‘temporary’ to help manage any difficulties staff/pupils may feel adapting to them initially. But it is essential to acknowledge and name the potential feelings that these ‘new norms’ may create in both staff/pupils and in relation to groups (e.g. friendship groups, staff groups, parent communities, dinner ladies etc). Psychological safety in groups is created by an environment that encourages people to express their opinions. School leaders need to provide space for feelings to be discussed, because having the ability to raise honest concerns allows groups to adapt to the context and recognise when change is needed. A useful way of discussing change is through using group processes such as Edward Debono’s 6 thinking hats (http://www.debonogroup.com/six_thinking_hats.php), a way to deconstruct thinking positions whilst depersonalising minority views.

Focus on certainty and predictability

As school leaders it is your role to hold and contain the emotional and physical needs of the school community. Where possible, help staff and parents to recognise what has not changed, and what remains the same. Predictability and routines have a stabilising effect on people’s emotional well-being. Clarifying routines and expectations which will remain be the same should therefore have an anxiety-reducing effect.

Develop a communication strategy

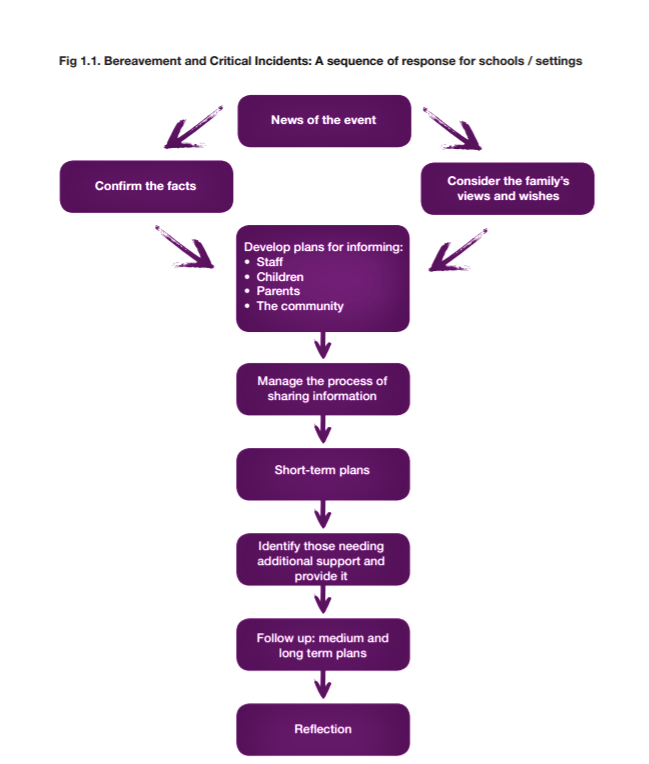

Staff and parents will need information quickly sometimes, but they also need it ‘filtered’ and delivered through appropriate channels. Limit ‘knee-jerk’ texts or emails where possible, until you have defined decisions as a leadership group. People’s sense of perceived threat is already heightened, so it is important to share decisions only when they have been made, and to give people the option of ‘reading’ information when they are ready to. Be honest about things you know, and don’t yet know. Decide who needs what information and when. A helpful go to model for managing a response to crisis in schools is provided by Bracknel Forest Council (Coronavirus and Bereavement);

Locate and promote your school’s resilience factors

Schools are usually very resilient places, where ‘change’ is often felt and managed quickly. Your school will already posses the key strengths, skills and creativity to manage and overcome emotional/physical challenges. Notice them, talk about them. Make references to previous ‘chaos’ that you have overcome. How did you do this? What helped? Strengths based psychology, including the use of gratitude, hope and optimism is helpful for creating behavioural shifts when individuals and organisational are managing change/threat (Cooperrider et al 2008). A useful approach to process change as a staff team, might be through the use of Appreciative Inquiry (Cooperrider et al 2008), which most educational psychologists have experience in supporting.

REFERENCES

Bracknell Forest Council; Cornavirus and Bereavement; Support for schools/settings/ parents and carers. (http://search3.openobjects.com/kb5/bracknell/directory/service.page?id=Lnfoi-MpIcc)

Cooperrider, D. L, Whitney, D. & Stavros; (2008) Appreciative Inquiry Handbook For Leaders of Change (2nd Edition), Crown Custom Publishing.

Festinger, L; (1957) A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press

Garcia, T., Massoni, S. & Villeval, M. C. Ambiguity and excuse-driven behaviour in charitable living. Eur. Econ. Rev. 124, 103412 (2020).

Gino, F., Norton, M. I. & Weber, R. A. Motivated Bayesians: Feeling Moral While Acting Egoistically. J. Econ. Perspect. 30, 189–212 (2016).

Powell, T, P., & Enright, S,J., Anxiety and Stress Management, London and New York Press (1993)

Van Bavel, J., & others; Using Social and Behavioural Science to Support COVID-19 Pandemic Response (2020)

Van Lange, P. A. M., Joireman, J. & Milinski, M. Climate Change: What Psychology Can Offer in Terms of Insights and Solutions. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 27, 269–274 (2018).