The Emotional Impact of COVID-19 on Children: Psychological Insights for Schools

A key task facing schools as they transition back to school after the government imposed ‘Lockdown’, is being able to understand and respond to the emotional needs of their pupils, in ways which encourage stability and recovery. Some evidence suggests that more children will have been placed at risk during this period, given higher incidence of domestic violence. For example, calls to the Domestic Abuse Helpline rose by 49% the week after ‘Lockdown’, and killings in the home have doubled. Families continue to face pressures which might exacerbate relational difficulties. Irritability is high, and resilience maybe low. Alongside this, families are living with the potential threat of the virus, with some having experienced family losses themselves, alongside financial challenges. At the start of the pandemic in March 2020, a Young Minds survey revealed that ‘Lockdown’ had had a profound impact on children with existing mental health conditions, with feelings of increasing anxiety reported by 83% of over 2000 children interviewed. Other symptoms noted were sleep problems, panic attacks and increasing thoughts around self-harm (Young Minds Survey, March 2020). In response, Emma Thomas, Chief Executive of Young Minds, said:

“The coronavirus pandemic is a human tragedy that will continue to alter the lives of everyone in our society, and the results of this survey show just how big an impact this has had, and will continue to have, on the mental health of young people”.

It stands to reason then, that schools will need to equip themselves with knowledge and skills in the area of trauma-informed practice more than ever before, and that the plight of those children who have already experienced traumatic early histories must be the key focus for school leaders and teachers. However, until children are ‘back to school’, much remains unknown as to the emotional and psychological impact of COVID-19 on children and young people as a whole. A few key considerations for school leaders and teachers are discussed here to support their preparations and planning;

1. Explore emotional health and well-being

Some trauma specialists have gone as far to say that society as a whole is undergoing ‘collective trauma’ as a result of the pandemic, (e.g. Bomber 2020). In Louise Bomber’s webinars, she describes the sustained presence of the coronavirus as the experience of a collective threat. As a result, our nervous systems are likely to be on alert, with a higher preponderance for low level fight/flight reactions to environmental stressors etc. Bomber makes the useful link between the 7 preconditions of trauma (Van der Kolk 2014), and our experiences of COVID-19 and ‘Lockdown’, which will apply to teachers, parents and children alike;

- Lack of predictability

- Immobility, fear and powerlessness,

- Loss of communication and connection

- Numbing

- Loss of safety/time

- Loss of safety

- Loss of purpose

Whilst mental health risk factors are likely to have increased for our children during the period of ‘Lockdown’, early behaviour theorists remind us that behaviour is a function of both our personality traits and environmental influences/resources (Lewin 1935). Whilst one person might develop symptoms of depression or anxiety following a traumatic event, another person might not report any symptoms at all for example. Therefore, how children attribute meaning to events is important to consider when determining the psychological impact of collective threat over time. Moreover, and according to cognitive behavioural science, it is the interaction between a person’s beliefs, feelings and thoughts in relation to a traumatic event that leads to either adaptive or maladaptive coping mechanisms, not the event itself. It seems useful then for schools to check the ‘emotional temperature’ not just of the vulnerable, but for all children returning to school. Some useful resources to consider are;

- Back to school wellbeing questionnaire, ELSA Support; https://www.elsa-support.co.uk/back-to-school-wellbeing-questionnaire/?fbclid=IwAR1Yu8Fn79qPPSB_1h9oXYjH1sPRmkRwsvx8Vbma1QI4bntGqsppLSEZBOY (Early Years and Key Stage 1)

- Pupil Attitudes to Self and School (PASS), GL Assessment; https://www.gl-assessment.co.uk/products/pupil-attitudes-to-self-and-school-pass/ (Key Stage 2/3/4)

- Emotional Literacy Assessment and Intervention, Southampton City Council (Faupal 2003) (Key Stage 2/3/4)

2. Consider the System Around the Child

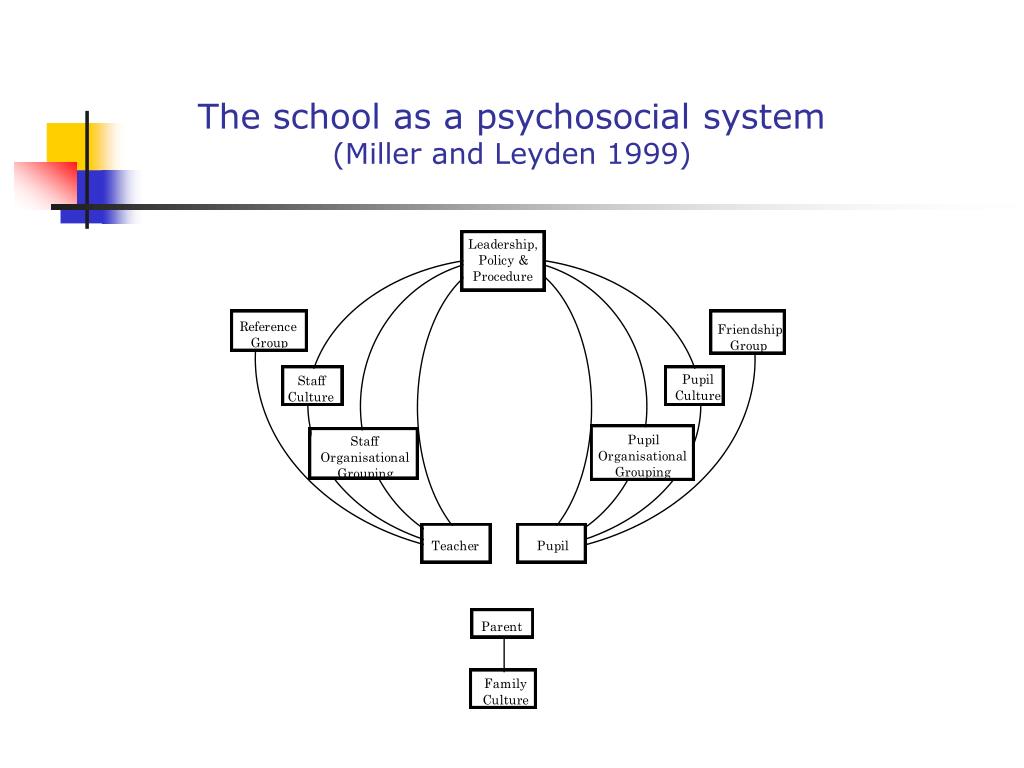

Whilst assessment of children’s emotional needs prior to their full return will be advantageous, the likelihood of schools being able to gather accurate whole-school data is unlikely. We also know that for some, their difficulties may emerge over time as the school structures slot back into place, because behaviour is understood as a response to our environment. According to system theorists (e.g. Bertalanaffy 1968), attempts to study ‘one part’ of the system in isolation will provide an incomplete picture, because the parts are interconnected and ‘greater than the whole’. In their ‘psychosocial system’ (above), Miller and Leyden (1999) demonstrate that there are a set of recursive interactions primarily between student, teacher and parents which can be thought to be ‘surrounding’ pupil behaviour. In essence then, whilst the primary goal maybe to ‘support children’s mental health’ upon the return to school, ignoring the impact of parents/staff wellbeing on children’s presentation should be avoided.

a) Support Parents and Carers

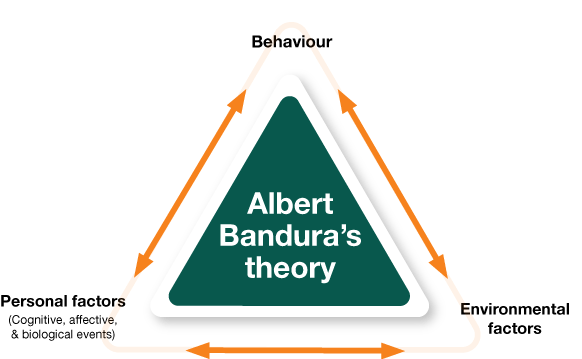

Social psychology studies indicate that children’s behaviour is largely influenced by what they see role models doing (Bandura 1977), therefore we can probably expect that for those parents who feel anxious, their children will too, and the same goes for other strongly felt emotions. In times of national crisis, evidence also suggests that different segments of society are likely to arrive at different conclusions about what ‘appropriate actions’ they should take. Indeed, when people’s psychological needs are frustrated (e.g. potentially as a result of increasing isolation and limited self-control) alternative narratives such as conspiracy theories can become attractive (McCauley & Jacques 1979). The polarisation of views will mean that for school leaders trying to drive ‘collective action’ there is likely to a be a continuum of responsiveness, both at the child and parent level. Absenteeism, in-action or despondency are likely reactions of some families and communities, yet there will be high levels of stress, anxiety and maladaptive coping in others.

Whilst engaging parents is nothing new for schools, (and is already part of their planning for the school return), there appears to be stronger reasons for generating conversations about their wellbeing right now, if we want to effectively plan for children’s emotional recovery moving forwards. Some ideas to support school leaders are;

Personalise contact;

The more personalised the communication channels with parents, the more likely there will be connection and concordance according to behavioural/social psychology research. Nudging statements e.g. ‘the overwhelming majority of people in our community people feel that…’ tend to create behaviour shifts at times of crisis, more than coercive measures such as legally imposed or directive policies (e.g. Van Bavel et al 2020).

Focus on the majority;

Conformity research tells us that people are more likely to cooperate when they believe others are (Asch 1961). People also tend to be highly reactive to choices made by trusted others. Social media might therefore play an active role for schools in supporting shifts in expectations; it could be a place to demonstrate cooperation and resilience in your school community, rather than a forum to deliver information only.

Safe space;

Supporting parents and carers with their emotional wellbeing at this crucial time will be money well spent. Build into your planning the idea of parent workshops around stress/anxiety management, or parent ‘drop ins’ to support any queries as they arise. Use school psychologists and counsellors in a consultative capacity to help support the emotional needs of parents/carers and link with family liaison/charitable organisations where appropriate. Whilst many parents might not take up the offer, they will be comforted by the presence of a ‘listening organisation’ at times of uncertainty.

b) Support and Prepare Staff

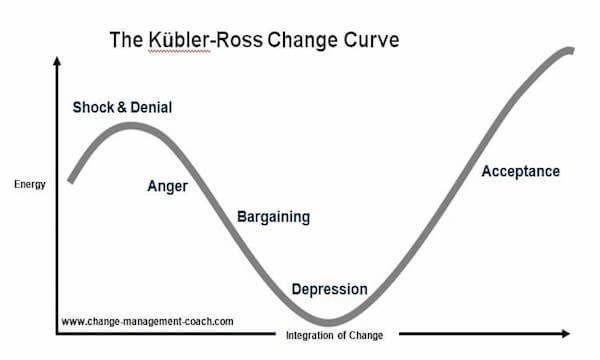

As children return to school, the teacher’s sense of safety and wellbeing can not be under-estimated. Yet their mental health will have also been affected by the uncertainties and changes thrust upon them, and they are likely to be at different stages of the cycle of change themselves (e.g. Kubler-Ross 1969). Drawing upon attachment theory (Bowlby 1969, 1988), Heather Geddes (2006) describes how schools can act as a ‘secure base’ for children, offering the protective factors which might otherwise be absent at home. Upon returning to school therefore, children will benefit most from adults who can demonstrate the characteristics of a ‘secure adult’ e.g. attuned, consistent, available, predictable, sensitive, nurturing and responsive. The ability of teachers, support staff, mid-day-supervisors etc to be able ‘relate’ and connect is imperative to help children develop a sense of belonging and re-connection with the school community. It is from this point that children can explore and learn confidently.

It goes without saying then, that where staff feel anxious or stressed, or have unmet emotional needs themselves, they may convey a lack of emotional availability to those around them. For children who may already be hypervigilant to adult emotions, (e.g. for their own survival), their sense of psychological threat may therefore become even more heightened. As Van der Kolk (2014) argues, the vulnerable will show their story. If children are not feeling safe, they will give meaning to situations or expressions based upon their previous experiences. For example, when feeling heightened levels of fear, children may interpret a sound, a face, a phrase as threatening. More broadly, the common difficulties expressed by traumatised children are described by Hughes, Golding and Hudson (2019) and include;

- A mistrust of adults, e.g. to keep them safe

- A limited sense of self

- Being easily confused, easily led, disorganised, and with no direction

- Showing a focus on getting their needs met, and limited engagement with little else

- A lack of curiosity in others and the world around them (focus is to stay safe)

- A lack of self- awareness as to their own strengths and needs

- Responding to stress/challenge in unpredictable or impulsive ways

- Likely to lack skills to facilitate their own development

Needless to say, if children’s emotional needs remain unmet, the impact on teaching and learning will be significant. As Hughes et al 2019 explain; ‘when an individual feels under threat, they are not concerned with learning about the world or developing the self- because the focus is on survival in a habitually defensive state’. Creating an emotionally attuned and responsive staff team is therefore crucial to supporting children’s recovery in the short-medium term. Some key thoughts for school leaders might be;

Re-clarify support systems for staff;

It is important to check the emotional temperature of staff teams too, many of whom have been working since ‘Lockdown’ and/or managing their own family challenges/stresses. Teachers need a space to have their own personal/professional journeys recognised, to develop self awareness as to the impact these changes have had on them, and a chance to explore their coping strategies for managing stress/anxiety moving forwards. When staff teams are back together in some physical capacity, school leaders may want to use whole team sessions to map the journey so far, shape a new future together, and identify strengths in the school system moving forwards. This will indirectly help school leaders to develop a community of staff who are ‘in this together’, an effective leadership approach at times of crisis and uncertainty. Several problem solving tools can assist whole school planning (see Inclusive Solutions). Orange Psychology has also prepared some Collective Recovery Workshops to assist schools in this area (see Workshop 1/2).

Avoid focusing on ‘catch up’ too soon;

Many theorists in the area of trauma-research are warning that children will not be ready to pick up where they left off cognitively or academically. Yet we know the pressure for performance in schools has not abated. The neuroscience of trauma imaging tells us thought, that the brain needs time to repair from anxiety and stress (Van Der Kolk 2014), through relationship/connection and regulation (Dobson & Perry 2010). Children cannot move to higher parts of brain functions (e.g. rationality and reasoning) before these stages are supported. Schools will need to think through providing a curriculum which is therefore focused on recovery, which embodies the principles of relationship and regulation before attempting to reintroduce the pace of the curriculum as it previously was (e.g. Barry Carpenter 2020).

Focus training around Trauma Informed Practice;

During the transitional of children returning to school, it seems ever critical to equip staff with greater knowledge, skills and confidence in the area of trauma informed practice. There are a variety of places to seek training in this area nationally (e.g. Touchbase), but is also a focus of many local psychology/therapeutic services including our own ‘Collective Recovery Workshops’ offered to schools (e.g. Collective Recovery Workshop 2/3)

In summary, whilst we do not yet fully know the emotional impact of COVID-19 on children, we have some clues based on social indicators and our understanding of the impact of trauma in childhood. Whilst one size won’t fit all and not all children will be ‘traumatised’, we still need to respect each child and family’s experiences. We need to provide a listening space for the system around the child, and to provide connection and co-regulation for those most at risk. As Louse Bomber (2020) emphasises, we must go slowly.. there is no rush. Time and sensitivity will be needed to understand and notice how children are responding upon their return, with informed and responsive teaching staff who have skills to help children to manage their feelings safely.

References

Asch, S. E. (1961). Issues in the Study of Social Influences on Judgment. In I. A. Berg & B. M. Bass (Eds.),

Carpenter., B. (2020) Launching the Recovery Curriculum; https://barrycarpentereducation.com/2020/04/23/the-recovery-curriculum/

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change.

Bomber. L., M. (2020) Series of trauma informed webinars https://touchbase.org.uk/support-through-this-season/; Touchbase

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Loss. New York: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1988). Attachment, communication, and the therapeutic process. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dobson, C. & Perry, B.D. (2010), “The role of healthy relational interactions in buffering the impact of childhood trauma in “Working with Children to Heal Interpersonal Trauma: The Power of Play,” (E. Gil, Ed.), The Guilford Press, New York

Faupal, A. (2003) Emotional Literacy Assessment and Intervention, London, Southampton City Council, Nelson Publishing Company Ltd.

Geddes, H. (2006) Attachment in the classroom: A Practical Guide For Schools: Worth Publishing Ltd

Hughes, D.A., Golding, K.S., & Hudson. J., (2019) healing Relational Trauma with Attachment-Focused Interventions: Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy with Children and Families. W.W. Norton & Company Inc.

Lewin, K. (1935). A dynamic theory of personality. New York: McGraw Hill.

Kubler-Ross, E. (1969) On Death and Dying. Macmillan, New York.

McCauley, C. & Jacques, S. (1979) The popularity of conspiracy theories of presidential assassination: A Bayesian analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 37, 637–644.

Miller, A. & Leyden, G. (1999) A coherent framework for the applications of psychology in schools; British Educational Research Journal, 25(3); 389-400

Pupil Attitudes to Self and School (PASS) https://www.gl-assessment.co.uk/products/pupil-attitudes-to-self-and-school-pass/

Van Bavel, J., & others; Using Social and Behavioural Science to Support COVID-19 Pandemic Response (2020)

Van Der Kolk., B. (2014) The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin

von Bertalanffy, L. (1968). General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications. New York: George Brazille

Young Minds Research (March 2020); https://youngminds.org.uk/about-us/media-centre/press-releases/coronavirus-having-major-impact-on-young-people-with-mental-health-needs-new-survey/